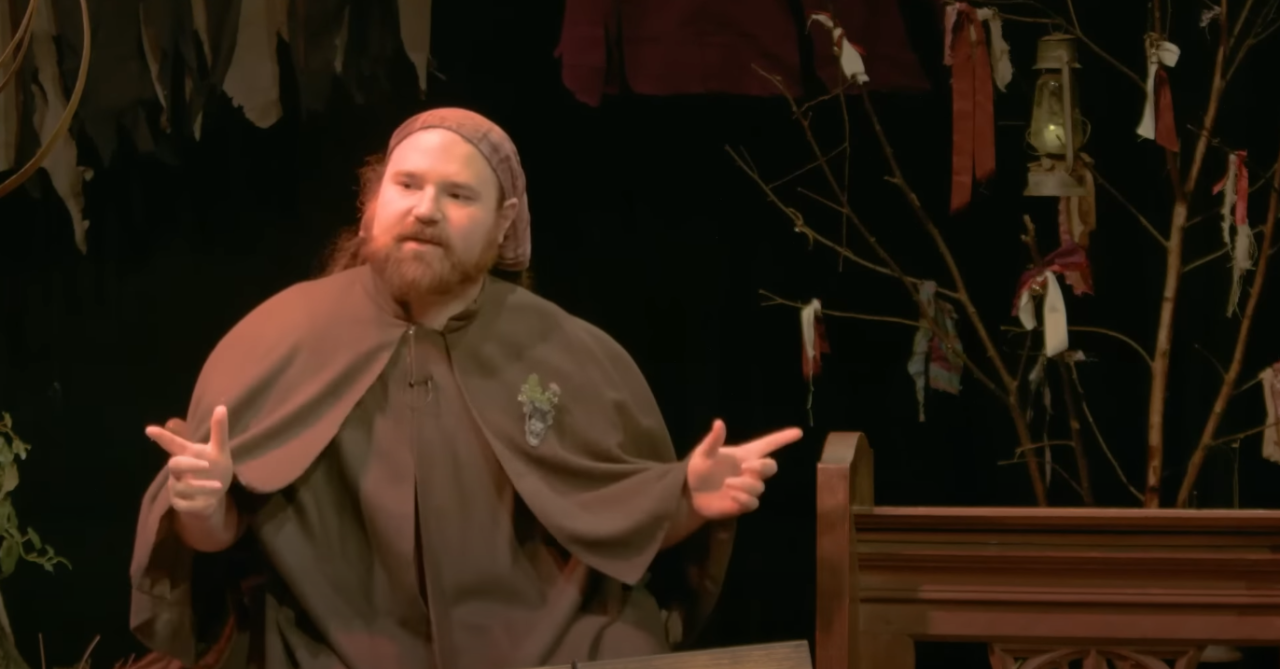

Ten days ago, Steve asked me, in the kind of oddly-specific-yet-simultaneously-open way that only Steve can, to write an article about my journey to becoming a good storyteller. To be honest, my immediate thought was that I’m not really that good of a storyteller. I can think of a dozen STs who have a better grasp of the rules than me. Certainly, if you read any of the comments on the No Rolls Barred Plays Blood on the Clocktower videos, you’ll learn that I am instead an incompetent, evil lizard-man from outer space, who is here to steal the sun.

So I spent the next week mulling it over, gathering all of the handy tips and tricks I’ve learned over the years. I was preparing to talk about how you should always double-check your grimoire at the end of the night phase, to ensure you haven’t missed anything. Or perhaps explore how certain combinations of characters can leave avenues of bluffing open for the evil team. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that simply knowing the rules and having a bunch of strategies in your mind is not what makes a good storyteller. So here’s the story of how I became a ‘good’ storyteller.

I first came into contact with Blood on the Clocktower in the summer of 2018. At the time, I was working as a freelance games journalist, trying to get my writing career off the ground, whilst also managing a board game cafe in the English city of Derby. One of our favorite things to do at that cafe was to wait until closing time, and invite anyone who was still there to join us for a lock-in. Then we’d grab a few beers and play social deduction games. Classics like Werewolf, Avalon, and even Cosmic Encounter would regularly see the table during those beer and bluff fuelled evenings.

When the owners of the cafe announced we’d be going to the UK Games Expo, I decided to check out what cool stuff would be there and that’s when I saw this video on the UKGE’s website. I was utterly blown away. A social deduction game, like Werewolf, with no elimination, in which evil characters can cause good characters to get false information. Seeing it was like having some sort of switch flipped in my brain and I found myself wondering how I could ever go back to enjoying Werewolf again, now that this clearly superior set of mechanics existed. ‘It must be horrendously unbalanced or something’ I thought to myself. ‘There’s no way you can run a game like this without elimination.’

So we rocked up to the UKGE and I immediately made my way to this tiny trestle table that housed Blood on the Clocktower’s little corner of the con. Sat behind it were two Aussies, who I’d later come to know as Evin and Sarah. I immediately started gushing to them about how cool I thought their game was, and how I couldn’t wait to check it out. In my excitement, it hadn’t actually crossed my mind that this game might be a very small, completely unreleased indie venture, by a bunch of total game-producing noobs. I just assumed it was an already established product that had passed me by somehow. Consequently, when I started fan-boying over them, they were completely taken aback and probably a bit terrified! Nevertheless, I came back to the booth over and over again during the weekend to keep trying out the game. By the end of the con, I was utterly converted and asked if I could get involved somehow. They were so delighted by how enthusiastic I was that they offered to send me a prototype copy. Thus began my journey from chubby, hairy nerd to chubby, hairy nerd who is also a storyteller.

In the following months I would run a bunch of games, mostly at our board game cafe. It quickly became apparent to me that I couldn’t treat Blood on the Clocktower as though it were Werewolf. By which I mean that I couldn’t simply be a referee or an adjudicator of some kind, disconnected from the activities of the players. Because the game requires input and mechanical decision-making from the GM, it can’t be run like a team sport or a competitive tabletop game, it needs to be a narrative, role-playing experience.

It was generally the same group of people that played each week, so I began to focus almost exclusively on the social dynamics of that group. When announcing a death I wouldn’t simply say “Lydia died in the night”. I’d instead say something like “you’re all going to be shocked to hear this, but it looks like Lydia might not be on the evil team for the first time this month, because she somehow perished in the night.” I’d flap about like an idiot, waving my arms around as I spoke, raising and lowering my tone in a ham-fisted attempt at dramatic expression. And do you know what happened? Everyone had a good time…even when the game itself was crap, usually due to me screwing things up. I came to understand that, unlike every other game I was running, the role-playing experience in Blood on the Clocktower came not from playing the role which the game assigned you, but from the role which the group’s meta assigned you. Always-evil Lydia, through no decision of her own, had become the group’s megalomaniacal, evil genius. When she died in the night, it was our group’s micro-version of Darth Vader’s “I am your father” or (spoiler alert) Ned Stark’s execution. It surprised people.

I’ve often asked myself why that group always had such fun, particularly when so many other social deduction games have a reputation for being toxic and unwelcoming. I think it’s ultimately because my players were enjoying one another’s company at least as much as they were enjoying the game. They were humanized in each other’s eyes and that meant that, no matter how good or bad the game was, they were always going to have a good time. In much the same way that when you go out on a weekend, you’re not there just to drink beer, you’re not there just to listen to the music in the bar, and you’re not there exclusively to have a conversation with friends. It’s the combination of all of these things that you’re enjoying. So when the tunes are crap and the beer tastes like piss, you can still have a good time.

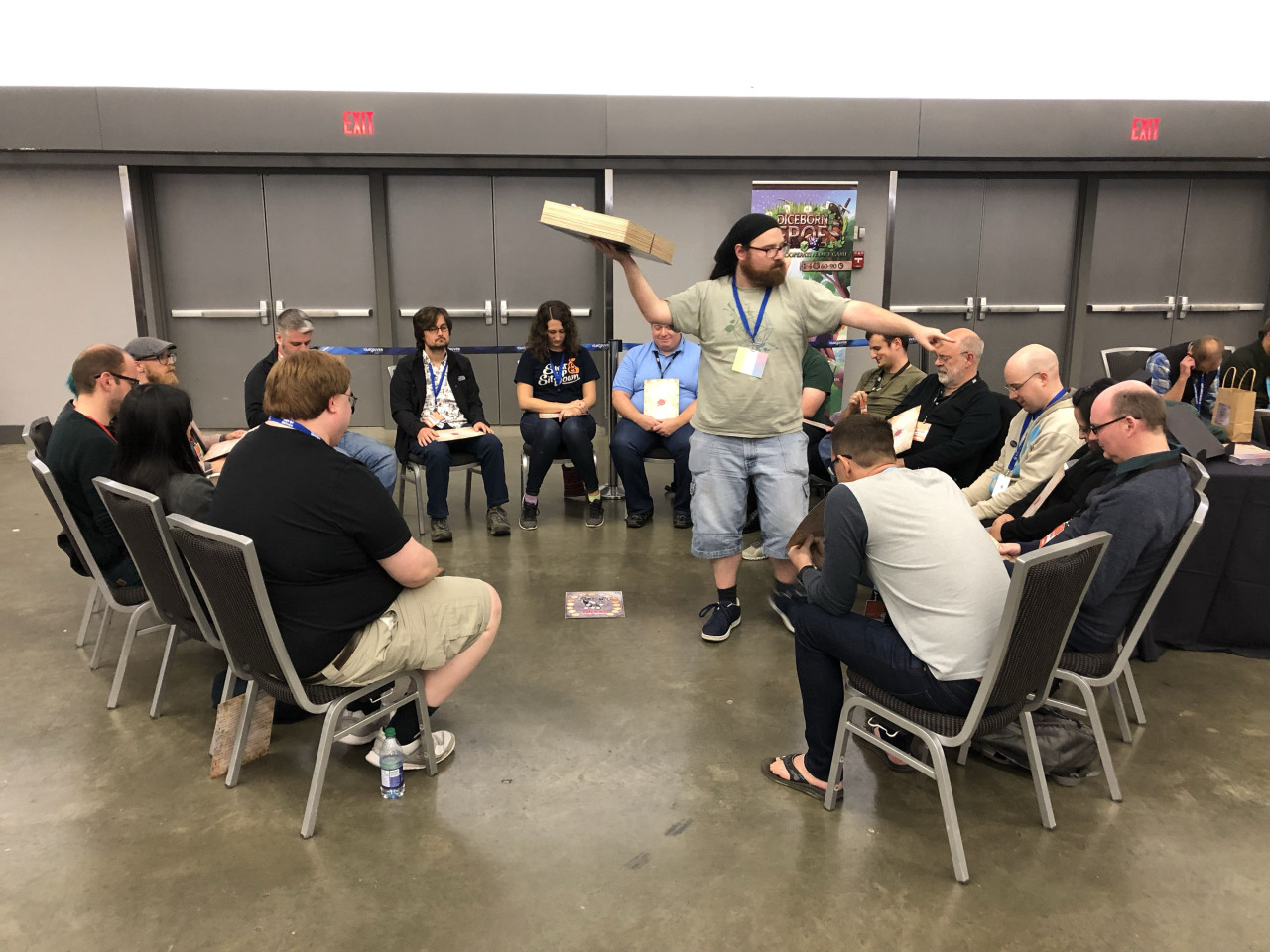

By April of 2019, the game had experienced an insane Kickstarter campaign, having achieved almost 1000% of its funding goal. I felt like I could be more than just an enthusiastic fan, so I spoke to Steve about becoming a more permanent part of the team. Sure enough, I was welcomed in and started regularly running games at conventions.

Now it’s easy to ensure your players have fun when everyone knows one another. But at a convention you’ve got nine total strangers, all with different ideas about what makes a fun game, probably all with massively divergent expectations of the kind of social conduct they’re comfortable with. Yet you’ve somehow got to ensure they all have fun whilst arguing with one another and accusing each other of being deceitful liars. I don’t think many people appreciate just how truly difficult it is to be a GM at a convention.

So I applied what I’d learned from my time running for friends. These people were not a group of familiar pals with a meta and an idea of each other’s personalities, so I simply decided to make them into that over the course of the game. “Good morning everybody” I’d say, as I pointed to Dave with his Metallica t-shirt on. “I’m afraid we’ve now learned for whom the bell tolls. It looks like it wasn’t the sandman who visited Dave last night!”

Now this might seem like a shit Metallica pun, from a circus clown, with an overrated sense of his own comedic genius. And that certainly is what it was (har har). But it served an important purpose. To the other attendees in my game, Dave was no longer just some stranger at a convention who happened to be playing with them. He had become Dave, the fan of heavy metal, the guy whose death made us all laugh. As for Dave, who sadly died first, something which could easily make someone with a less charitable personality upset. He now associated his death with a joke, with everyone smiling, and with the GM showing that he too enjoys a bit of thrash metal.

Over the course of that game and many others I ensured that when I spoke to the players, it wasn’t about what was mechanically happening behind the grimoire, but on what was physically happening in the town square. I’d compliment people for boisterous and impassioned accusations, or logical and well-articulated defenses. I’d pull random players aside from time to time, to ask them if they were enjoying the game or if they had a theory on who the demon might be. To put it bluntly, I spent my energy on letting them know that I was having fun and that I wanted them to have as much fun as me. From my time touring in bands, I’d learned that in 99% of situations, if the band were clearly having fun, the audience would too. I’ve seen bands that could barely play their instruments, utterly captivate an audience, all because they were visibly having a blast. I’ve also seen absolute maestros totally tank on stage, because they were clearly not into what they were doing.

And therein lies the essence of good storytelling, or at least my peculiar version of it. It isn’t about knowing the rules, although that certainly helps. The main ingredient of good storytelling is right there in the name of the role. Spin a yarn, make your players feel invested in each other and in you. It doesn’t matter how you achieve this, and you’ll certainly find a way that works for you. My buddy Edd, for example, has created a Spotify playlist full of songs that relate to the game’s characters, such as ‘Poison’ by Alice Cooper and ‘Moonchild’ by Iron Maiden. He uses it to cover up the sound of him moving around during the night phase. Whenever I close my eyes and hear some cheesy song that is tangentially related to BOTC, blaring out, I’m reminded that this guy is having so much fun playing Clocktower that he sat down and created a 100 song playlist, exclusively for use during a 90-second portion of the game.

So…have fun, enjoy your players, and most of all, don’t worry. If you’re enjoying yourself and if they’re enjoying themselves, you’re doing absolutely fine!