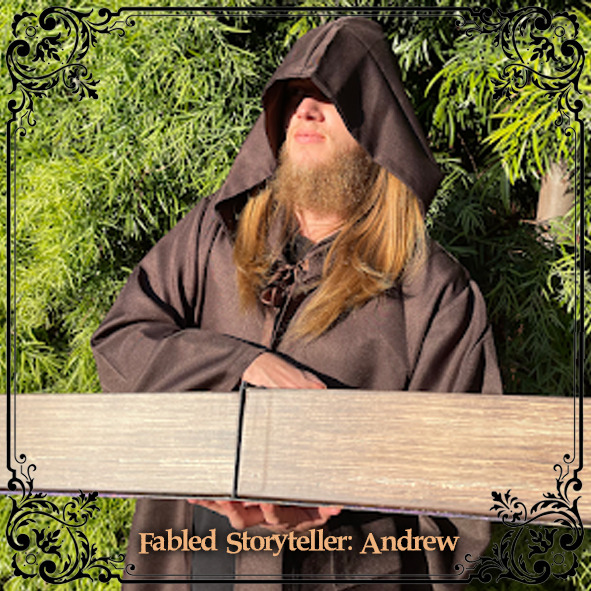

Thoughts on the game from Cult of the Clocktower podcaster and friend of The Pandemonium Institute, Andrew Nathenson.

-

In Blood on the Clocktower, good players can receive misinformation for a large number of reasons. One of the most common refrains to hear while playing is “…or I could be drunk or poisoned.” This good-sided misinformation is something of an anomaly in social deduction games, breaking a key expectation that many bring to the genre: players giving out misinformation are evil (or spies, or Minions of Mordred, or Fascists, or whatever else the informed minority is called). In many games, identifying misinformation is key to identifying who are the baddies. Any information that the good team has is meant to be directly used to figure out who is bad. So this leads to a very natural question about BOTC: if, as a good player, my information is unreliable, how am I meant to use information to learn anything about the game? Or, less generously, the comment: there is no way to use the information that is given to solve the game, so you might as well not have information in the game at all.

Hi. My name is Andrew Nathenson, and I have played/Storytold several hundred games of Blood on the Clocktower. I have a podcast about BOTC strategy called Cult of the Clocktower. I recently started volunteering for The Pandemonium Institute, the company that makes BOTC, and I’m one of their 12 “Fabled” storytellers; basically, an ambassador for the game. What I’m trying to get at is that I’m a somewhat biased source. I love this game so much, and have developed connections to it beyond just as a player. But I also am one of the most experienced players of the game in the world, and have devoted more time toward studying it than any sane human should. So, keep all that in mind when I say: Blood on the Clocktower is fundamentally a strategy game, not a social deduction game.

Okay, that’s a bit of an overstatement. It’s a social deduction game of course, but it has a much, MUCH deeper strategic layer than almost anyone gives it credit for, including most people who love the game as much as I do. I hope that after reading this essay, you will see at least a little bit more of those depths.

This essay is intended for people already familiar with Blood on the Clocktower. I’m going to assume you know the rules and terms I’m using.

The Evidence

Before I do any analysis of the strategy in the game, I want to start with some data. It’s data only from my perspective, and it’s about my perception of what was happening in the games, not something traceable like the winner of the game. Nevertheless, it is something I’ve actively kept track of, so it’s slightly better than anecdotal.

I’m not sure exactly how many games of Clocktower I’ve played (not Storytold), because I didn’t keep track of my game plays when I started. I mostly Storytell, as the most experienced player in almost every group I’m in, so it’s not a ton. Let’s say I’ve been a member of the good team for around 50 games, though I’m sure it’s a lot higher than that.

There have been exactly three games in which I have lost and incorrectly thought that a good player was evil at the end of the game (voted for them).

So, do I have a 94% winrate as good, then? No, certainly not. There have been many games in which I’ve known who the Demon was, but the rest of the group wanted to execute someone else (me, for instance). Many times, I’ve convinced the town to execute the player I wanted them to, but they turned out to be a Minion. Often I’m wrong about who is evil, or on the fence about it if it’s in the midgame, but the rest of the town overrules me and executes the Demon correctly.

The point I’m getting at is that in ~95% of games, either I have been able to use the information available to deduce a living evil player by the end of the game, or the rest of the town has been able to do so if I haven’t. Notably, “living evil” is not the same as the Demon, but I usually don’t feel too bad about accidentally executing a Minion, and I think this is still much more than most people would expect is possible. I don’t believe that I’m exceptionally good at reading people socially (in fact, I think I’m often quite bad at it; I’ve almost entirely stopped trusting my gut in this game, instead relying on my deductions). So, I think this evidence suggests that the game is often close to solvable, if you are a strong player who can successfully guide who gets executed.

That last part is really important. A lot of why I’ve been able to know who is evil is because I can convince my teammates to execute my other candidates first. This may not be a luxury everyone has, because there’s no guarantee the group will listen to you. But because of my knowledge of the game, I can make very good arguments to support what I want to happen, and I’m typically happy to be executed myself if it gives me more control over future executions.

This is where the strategy comes in.

Where does information come from?

Imagine a game of Trouble Brewing in which the good team consists of the Washerwoman, Chef, Monk, Undertaker, Ravenkeeper, and the Drunk who thinks they’re an Investigator. The evil team is the Poisoner and the Imp. The Washerwoman learns that the Chef is one of two players, and the Drunk Investigator thinks that either the Washerwoman or the Undertaker is the Scarlet Woman.

On the first day, the Chef announces that they’re the Chef, and the evil players aren’t sitting next to each other. The Imp claims to be Mayor, and the Poisoner claims to be Soldier. The Investigator relays their (false) information as well, accusing the Washerwoman and Undertaker. The Undertaker and Washerwoman both claim their characters to defend themselves, and the group decides to execute the Washerwoman because the Undertaker could still get more info.

The Undertaker is poisoned the next night, and learns that the executed player was the Scarlet Woman. The next day, the Undertaker is executed as well. In the rest of the game, the Monk fails to save anybody’s life, and the Ravenkeeper is poisoned when they are killed, resulting in them learning that the Imp is actually the Mayor. The Poisoner is executed, evil wins.

This example is based on a real game I storytold, though I’ve simplified it a bit to reduce the player count.

Looking at this game, or playing in it as good, one could be forgiven for thinking that the good team was fed almost entirely false information, and had no chance to win. The Investigator, Ravenkeeper, and Undertaker all learned false characters. The Chef info doesn’t do a ton on its own. The Washerwoman could confirm that the Chef was good, but that didn’t matter when the Chef just died in the night anyway. The information that was given fit together well to paint a picture of a world with a Scarlet Woman, not a Poisoner, so there was little reason to suspect poisoning.

However, the game is riddled with large tactical and strategic blunders on the good side that directly caused most of the misinformation to exist. The evil team simply had to take advantage of them.

The Undertaker revealed their character immediately, making it very easy for the Poisoner to target them. The Ravenkeeper presumably did as well; or, the other players in the game made their characters obvious enough that the Poisoner ran out of other viable targets. The Washerwoman didn’t establish 2-way trust with the Chef, so it wasn’t possible to rule them out as the Scarlet Woman. If they could have been ruled out, the town would have had another early execution to possibly remove the Poisoner from play, or at least another Demon candidate. The Monk completely failed to predict the Demon’s kills. If any of these mistakes had been corrected, the Good team would have very likely received different information throughout the course of the game. So yes, while they had no chance with the information they received, they caused themselves to receive that faulty information.

(Yes, the Poisoner could have just gotten lucky; but getting that lucky would be something like a 1 in 25 games situation. It happens occasionally, but not enough to invalidate the broader point.)

This whole example goes toward answering the question: where does information come from? Clearly, some of the information comes from the Storyteller, whose choices decided what false information the players learned. All of the true information comes from character abilities. But one of the biggest factors in controlling what information is given throughout the game is how the good team plays: specifically, who they choose to execute, who they choose to target with their abilities, and how they choose to speak to the group or individuals in it.

After a game like the above, saying “the information didn’t lead to a solvable game state” is true, but misleading. Such a statement implies that the information is the entire game, or at least enough of the game to determine its outcome. It is not. The game is largely played in the process of getting the information, not just using the information that already exists.

What even is information, anyway?

So far, I’ve been treating “information” as everything that is told to a player by the Storyteller. However, there is a lot more that one can learn from the game than just that. I’ll quickly list a few things that I personally consider to be strong mechanical information to which logical deduction can be applied. These will be in the game no matter who is Drunk/Poisoned/etc.

1. Voting and nominating. While savvy evil players will be a bit tricky in their voting and nominating, such as voting for one another, there are some things you can rely on and watch out for. Minions won’t cast a deciding vote that causes their Demon to be executed (without a backup). Players who get a lot of votes must have been voted for by some evil players. Players who vote in ways that contradict their arguments are often evil. There are many things along these lines that can be gleaned from voting.

2. Who talks to who, and when. It’s very unlikely, for instance, for a Demon to be able to accurately bluff being the Undertaker unless they’ve had contact with a Spy or the group is being very open about what characters they are. You can accurately deduce the information “This player is the Undertaker” by concealing characters and watching who they talk to.

3. Deaths, and lack thereof. Bad Moon Rising teaches that who dies at night is strong information. However, this can be applied to any script. Watching who dies will tell you a lot, and a night of no death does as well.

4. Bluffs and claims. False information that is made up by the evil team is still information. Analyzing it to find contradictions is still useful. A lot of the skill in being evil comes from bluffing realistic information that can create reasonable worlds. Inexperienced players won’t be able to do this well, so one expression of skill in the game is analyzing information and catching these bluffs.

Now, one last point regarding information:

All good players’ information is true. Always.

What?? There’s no way. That Investigator learned that one of those players was the Scarlet Woman, but neither was.

Well, yes and no. All good players receive true information always, but only if you know how to translate it.

It might help to think about how we can encode this information more formally. For instance, we could say the Investigator learned something like:

“Player A is the Scarlet Woman OR Player B is the Scarlet Woman OR Player A is the Recluse OR Player B is the Recluse OR You are the Drunk OR The Poisoner targeted you.”

So, saying “Or I could be Drunk or Poisoned” is really a fairly accurate way of transmitting information, though a redundant one. This information is a lot less specific, but it is definitely true. And, by combining many such pieces of information, along with game rules/facts such as “Only one player can be poisoned each night” and “Only one player can be the Drunk,” you can eventually eliminate many of those possibilities. The skill comes from doing so quickly, and knowing which possibilities are so unlikely that they aren’t even worth considering.

This isn’t to say you’ll always be able to untangle the information and figure out who is Drunk, for instance. But I hope that it goes some way toward assuaging the complaint that “any information could be arbitrarily true or false.” The logical statement I put above is the full version of the Investigator’s info, and it will always be true.

Executive Order (the most common mistake)

One of the biggest mistakes the good team makes is just choosing awful executions at the wrong times. Even if you truly have no way to divine who the Demon is, you can at least execute players who might be the Demon to maximize your chances.

I’m not going to go into extreme depth here – this is a subject for a whole other essay – but I’ll try to get the main idea across with an example. A super common mistake I see: a Recluse is the only player claiming to be an Outsider in a game with 2 Outsiders by default. The town executes them. This is terrible, because that Recluse is mechanically guaranteed to be Good as long as nobody else is claiming to be an Outsider. You’re missing a chance to eliminate the Demon, a Poisoner, etc. A similar situation can arise when the town decides to execute a Washerwoman who confirmed themselves to a trusted player (though the Spy, for instance, can sometimes make this line of play necessary; as you may expect, there are plenty of caveats and exceptions).

Also, rarely skip executions. Executing is how Good wins. So many games that come down to a coin flip only do so because the town skipped an execution earlier in the game. I’ve lost a game by trusting a Mayor who turned out to be the Drunk, but it felt completely deserved because we had wasted an earlier execution, and otherwise would have only had one Demon candidate. Anyway, I’m getting a bit away from the original point about information in the game, so this is probably a good place to stop for now.

The overarching point of all of this: the information that is given to you doesn’t decide the game for you, the way you play the game decides what information is even available.

One last thing.

BOTC is a social team game. No matter how good you get at solving the puzzle, you’re going to sometimes just lose because you can’t convince your team to believe you or trust your logic; deduction and communication are two very different skills, both of which are essential to good play.